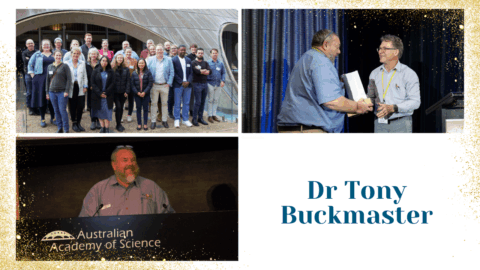

Farewell to Dr Tony Buckmaster: reflecting on RD&E milestones

Dr Tony Buckmaster, the Centre’s long-standing Principal RD&E Manager retired this month. Tony developed an enviable track record in invasive species research over several decades and influenced the development of best practice management, commercialisation pipelines and community engagement models while fostering a future generation of researchers.

Tony shared some reflections on his decades of experience working with CISS and its predecessors with the CISS Chronicle.

CC: Can you give a brief history of your career and time with CISS?

TB: I started as a PhD student in 2006 with the Invasive Animals Cooperative Research Centre (IA CRC). I was one of first students in the Balanced Scientist Program, as it then was. I graduated with the PhD in 2011 and started with IA CRC as the program’s coordinator. While I was in that role, I also did a post-Doctorate on rabbits. That took me into the second iteration of IA CRC.

I then started doing project management which included commercialisation as well as concluding aligned projects such as Blue Heeler.

CC: What prompted a career in invasive species?

TB: Although I come from an agricultural background, it wasn’t a driver for this career choice. In fact, I spent nearly 20 years as a public servant in the NSW court system as a Clerk of the Court and Coroner. I had gone to uni to get a law degree; I did a double degree in science law. The law didn’t challenge me, but the science did, especially ecological science. So, I dropped law and focused on the science. I was working on the antechinus around Canberra as part of my Honours project and started thinking about feral cat predation on native species and at the end of my honour’s year, the CRC was offering a scholarship. So, I applied and got that and that is what started me down the managing invasive species pathway.

CC: Tell us a bit about your career highlights.

TB: Leading the Balanced Researcher Program was a highlight. It saw 97% of participants complete their PhDs, compared to a national average completion rate of 60%. Not only that, 70% of our students have stayed in research and 60% have continued working in invasive species. Meanwhile, others have gone on to lead projects around the world as leaders in both environmental and human researchers on the international stage.

It was a privilege watching new PhD students coming in full of imposter syndrome and watching them develop into world leading scientists and leaders in their field. I still have the privilege of keeping in touch with them and seeing how they apply the learnings from the program.

Another highlight is clearly the research that came from both the CRCs and Portfolio No. 1 where we had the world’s leading researchers in their fields working collaboratively to find solutions to common problems. The quality and quantity of research that came out was just world leading. It was a major highlight to be part of such a massive collaboration with outstanding results.

CC: And your career lowlights?

TB: Watching the transition from good science being used to guide policy and decision-making to a paradigm where every opinion or idea needs to be treated as equal has been especially difficult. This can, and has, led to situations where opinion and ideas are being used to craft policy even though they are contrary to established science. This is problematic as we should be listening to opinions backed by an established body of science that can be replicated. It’s a dilution of replicable, established science by thinking that all opinions and ideas are equal regardless of the level of factual information that supports those opinions and ideas.

I’d also say that funding models have changed and not for the better. Funding for essential long-term research is generally no longer available. This stifles programs such as rabbit biocontrol that need to build, and continue to build on, knowledge and best practice over an extended period. It is worrying that “long-term research” is generally now the three years of a PhD research project.

For example, it takes eight to ten years to develop a new biocontrol for rabbits, but funding now goes for two or three years, maybe five if you are exceptionally lucky. Once that funding ends, staff need to move on and essential skills and knowledge is lost and hard to recover when additional funding becomes available later. Long-term funding of essential research pipelines needs to come back.

CC: Tell us about your fears for the future of invasive species’ impacts in Australia.

TB: We are winning on a number of fronts and we are doing best practice management of established species that is making a demonstrable difference. We are also seeing more species coming in and becoming pests. We are putting measures in to address that i.e. border controls and surveillance. We are always going to have those species coming in and we need to accept we are not going to eradicate established pest species, but we can, and are, managing their impacts.

I don’t have too many major fears: funding has always been a battle. I actually have a lot of hope rather than fears.

CC: Can you tell us some more about those hopes?

TB: I think there are new technologies and techniques that are going to emerge to help us deal with invasives and there are always new things to trial and investigate. For example, gene drive for rabbits. It is very exciting if it comes to fruition, but we have to remember that we have an estimated 20-year timeframe for that to be developed and we can’t stop existing activities like traditional rabbit control and developing a pipeline of biocontrols while we wait. We can’t stop what we are doing now in view of something that might happen in 20 years.

CC: What does retirement look like?

TB: It will involve spending time with the family and fishing but also not stepping out of the world of invasives completely. I want to become more involved in voluntary work and donating my time to Rabbit Free Australia. Like CISS, they are tiny but have massive impact.